BY Vasileios Zagkotas

Throughout my career in Greek Primary Education, I have encountered many students who struggled significantly with schoolwork. As a result, I would informally label these students as “weak” and try to help them adapt to the classroom teaching framework. I focused the main problem on their inability to respond to the language lessons, as I found that they could not read well and, therefore, were unable to understand texts and explanations. Although I tried to comfort their parents by telling them that “this type of school is not effective for these students because they think differently”, this was something I didn't really believe. I felt like I was chasing the chimera, that just as it was impossible for anyone to locate this mythological creature, so it was also impossible for me to effectively help these students.

The Chimera on a red-red-figure Apulian plate, c. 350–340 BC (Musée du Louvre)

By Lampas Group - Jastrow (2006), Public Domain

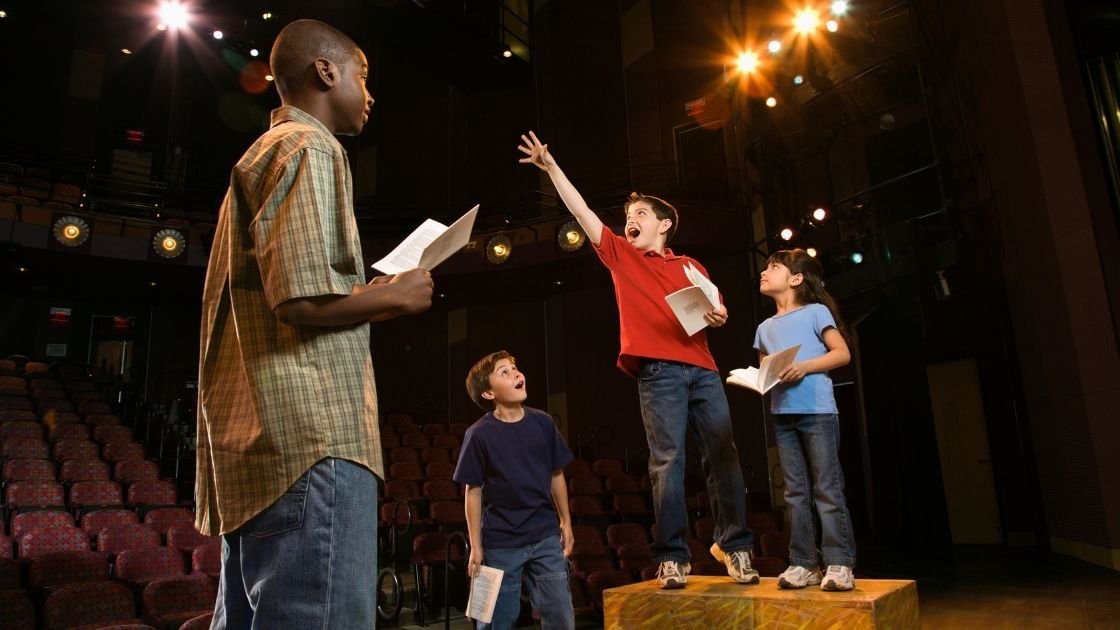

When I came across MI Theory, my perspective changed. The Greek educational system’s curricula and textbooks are focused on Linguistic and Logical-Mathematical Intelligence. Therefore, students who perceive the world in different ways tend to fail. MI theory convinced me to change my teaching practices. The first area I tried to help students was homework. I asked them to find musical pieces to accompany a linguistic or a history text, to dramatize a dialogue between historical figures, or to write a diary of emotions of a fictional character. The result was not exactly spectacular, but I gradually saw in these students a new willingness to participate in schoolwork.

A new role of Educational Counselor helped me move to undertake research on the applicability of the MI Theory. At a postdoctoral research level in the Department of Philology at the University of Ioannina, Greece, I designed a research project to apply MI Theory in secondary school homework practices.

I chose the field of homework assignments. I designed the research with a simple idea: teachers should make homework assignments based on MI Theory; students should work on them; teachers should record the students' responses, their comments and progress. Finally, the researcher should record his own reactions.

A significant issue was the relative unfamiliarity of many educators with MI Theory. I, therefore, created a tool that can be roughly translated as a “Toolbox of homework for the cultivation of Multiple Intelligences”. It consisted of eight tables—one for each type of intelligence—which provided educators with suggestions for assigning homework, such as “ask students to write an alternative ending to the story” or “to demonstrate a living picture” or “instruct students to organize a debate”, etc. The Toolbox was used in several educational settings. I identified willing volunteers and trained them informally.

I created a case study. All that was needed now was to train the volunteers, which I did myself by visiting the schools. I decided not to use any initial screening test for the “strong” and “weak” types of intelligence for the students. I was almost certain that the parents would be hesitant. Instead, I decided to use the tasks themselves as a means of assessment. I observed the students' behavior and performance during the activities, and I also collected their work samples. This allowed me to get a more holistic view of their strengths and weaknesses.

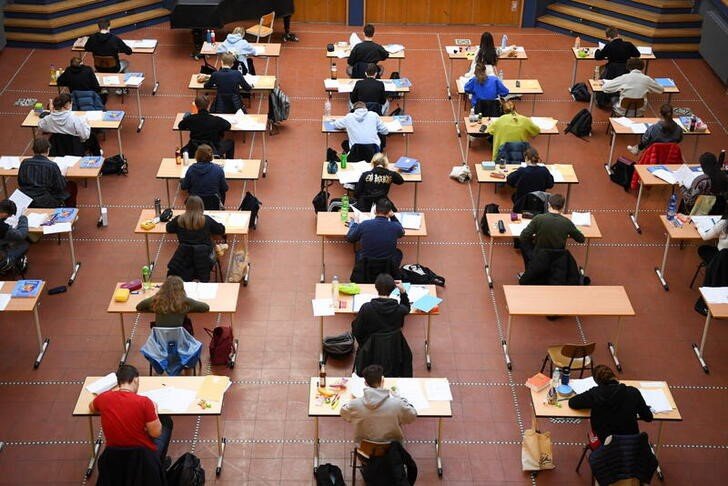

In the first phase, students completed a 15-item self-report questionnaire about homework. The results showed that students see homework as a way to understand what they learned in class and to prepare for the next lesson. They also believe that doing their homework makes them more acceptable to their teachers and helps them get good grades. However, they did not agree with the view that homework gives them opportunities to work with classmates, learn from them, and—to a lesser extent—cultivate character in their studies, such as self-discipline or systematic study. The same questionnaire was given after the completion of the research in order to investigate whether exposure to MI Theory changed their views on homework.

The teachers then used the “Toolkit” to get ideas and create worksheets for chapters of their choice. Some teachers chose Ancient Greek History, others Modern Greek Literature, and others Language (Ancient or Modern Greek). In the worksheets, they included tasks for each type of Intelligence. They then asked the students to work on no fewer than four tasks of their choice. I should note here that there were quite a few teachers who asked for my help—which I was pleased to provide.

A few sample assignments:

One teacher introduced “A Night at the Museum”. The students were given the following scenario: “The ancient Greek statues of the Kouros of Anavyssos and the Kore of Phrasikleia are placed opposite each other in a room of the archaeological museum. In a magical way, they can perceive what is happening around them but they cannot speak when there are visitors to the museum”. The students were asked to write a short diary of thoughts for each of the statues for a period of one week. The assignment was made available to the students, with the option of oral or written presentation and in pairs of boys and girls or individually. Additionally, the students could dramatize a dialogue between the statues when the museum is empty of visitors, in order for the representation of the statues' stances to help them understand the need for support of the statue (forward proposal of the foot). With this assignment, the students were asked to put themselves in the shoes of the statues and, through the interpretation of the statues' thoughts and feelings, to come into contact with their own feelings. Therefore, this particular assignment incorporated elements of Intrapersonal and Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence.

Dinos vase. Photo by Jastrow - Public Domain

Another assignment, drawing on Naturalistic and Spatial intelligences, asked students to paint a geometric and an archaic vessel (preferably an amphora, a pithos, or a hydria due to their large size) with scenes from Greek flora and fauna. Subsequently, they could create a small painting exhibition in the classroom. With this homework activity, the students had the opportunity to express their interest in the environment in a creative way. At the same time, they needed to research the characteristics and techniques of ancient pottery, adopting the shapes and patterns of the era. For this reason, this specific activity had a complex character, as students had to first consider the techniques and colors and then the theme of decorating the vessel. In my view students made meritorious creations. Some made videos: here’s one a: http://1gym-ioann.ioa.sch.gr/autosch/joomla15/draseis/502-zografizontas-to-mathima- tis-istorias.

The students' response to this and similar assignments was quite similar: at first they expressed confusion about the new type of homework, then they identified potential difficulties and finally they responded successfully, stating that they enjoyed it and that they would continue to choose such assignments. From interviews, we learned that teachers were able to detect some of the students' inclinations through their preferences. They found the “Toolbox” we created quite useful, but they also expressed the opinion that the new type of assignments does not favor the evaluation of students as it is done now, i.e. with grades in written exams. That point conceded, this research suggests that such a change is feasible and ought to be contemplated for the Greek educational system.

Such interventions continued for three months. The teachers concluded that the students improved their performance as they became familiar with the new type of tasks. The most important thing: several teachers emphasized that these tasks aroused the students' interest and that they participated actively in the process, i.e. they did the homework, even students who normally did not participate in the lesson. It seems, therefore, that the approach through MI constituted a successful path to an individual’s “entry point”.

Another important and unexpected finding: students who showed greater interest in the tasks created within the MI framework seemed to tend towards Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Intelligence. Specifically, they preferred to deal with diaries or to exchange arguments and, in any case, beyond the “paper/pencil” logic of school textbooks, which teachers themselves gradually began to view more critically. These developments pleasantly surprised the teachers. In addition, the questionnaire given to the students after the implementation of the “Toolkit” revealed a small increase in their interest in homework, but mainly a greater belief in cooperation between classmates.

Stepping back, from my experience as an educator, I know that few students like homework. Greek students are burdened with many extracurricular activities and their time is limited. I was encouraged by the results of this modest intervention. At a recent educational conference in Greece, I used some of these assignments to transform some chapters of the school history textbooks into an “MI-friendly” approach. The response of the teachers was touching. Many asked to learn more about the theory and its applications. Additionally, I seek to train as many teachers as I can in MI Theory and the possibilities it offers to get to know their students better.

In this text, I share my own experience and I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Howard Gardner for his overall interest, support and editing contribution. For the same reasons, I would like to thank his assistant, Shinri Furuzawa. Finally, the contribution and guidance of Dr. Ioannis Fykaris was invaluable.

As a result of this modest intervention, I feel encouraged. The more I examined the students' work, the more I came to believe in them. I realized, therefore, that the MI applications are not a chimera—rather an act of Prometheus, who gave the gift of fire to humans.

Research details:

Title of post-doctoral research: “The Didactic Contribution of Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences to the Structure and Organization of Homework in the Philological Subjects of the Gymnasium” (2024).

Author: Dr. Vasileios Zagkotas, Educational Counselor, Historian, Phd in Educational Sciences, University of Ioannina, Greece.

Supervisor: Dr. Ioannis Fykaris, Associate Professor, Department of Philology, University of Ioannina, Greece.