A few examples:

When we refer to a great cellist (like Yo-Yo Ma) or a great soprano (like Renee Fleming) as “smart,” it’s not that we are referring to how well that person scores on an IQ or SAT test. Instead, we might have in mind how quickly and how well that person picks up a new piece of music; or how well he or she analyzes a classical (or popular) work; or how the performer adjusts to the different conditions in various performance halls or with diverse ensembles.

When we refer to a great tennis star (like Arthur Ashe), or a great gymnast (like Simone Biles) as “smart,” we are unlikely to be referring to their grades in school. Instead, we might have in mind how quickly and how well that athlete adjusts to new weather conditions, new opponents, new rules of the game, an unexpected compliment, or an unfair criticism.

When we refer to a U.S. Senate majority leader or a House of Representatives Speaker as “smart,” we are not referring to their class rank in college. Instead, we might be referring to how the person manages to secure the votes needed to get a controversial bill passed or, depending on the circumstances, blocked…or how to position themselves vis-à-vis the media, reporters, cartoonists, or polls.

Even within the academy, this contextual use of the term smart prevails. Historians look for signs of intelligence that are quite different from those noted by economists, linguists, literary critics, biologists, mathematicians, or physicists. Scholars rarely comment in illuminating ways on the capacities of those working in fields remote from their own. We could say that a recognition of multiple forms of intelligence is spread throughout the academy, even among those who purport to believe in a singular intelligence, or IQ.

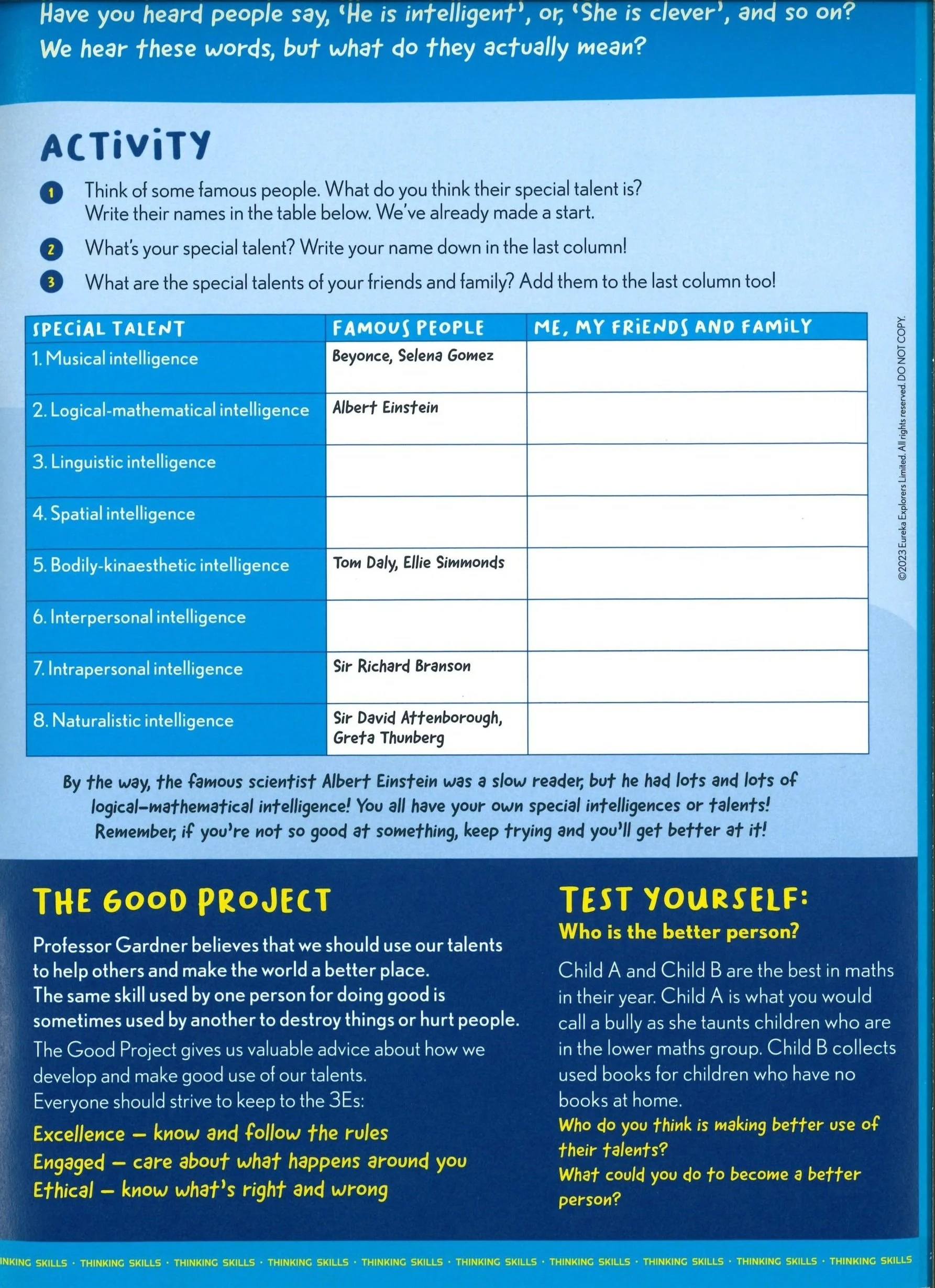

And so on—you can invent your own examples—whether from the ranks of clinical practitioners or weather forecasters or religious leaders or shop clerks. Nearly all of us are likely to continue using words like “smart” and “dumb,” or “clever” and “dull,” but we need to pick apart the field of reference of these words and make clear what we mean—and that requires the exercise of our personal intelligences!

Stepping back, after decades of pondering these issues, I identify three separate insights:

Human beings have a range of intelligences and we may, and sometimes do, change the ones that we valorize and why we valorize them.

Any intelligence can be used benevolently or malevolently; considered in themselves, intelligences are value-neutral. As masters of the German language, both the poet Goethe and the propagandist Goebbels had considerable linguistic intelligence, but they used it to very different ends. As human beings, we should be judged not by the intelligences that we happen to display and deploy but rather in which way we—and others—invoke them.

Even those of us who continue to use the words “smart,” “intelligent,” or “brilliant” need to stop, reflect, and recognize which of the intelligences we are actually valorizing—and why we do so.

And of course, the advent of ChatGPT and other Large Language Instruments will compel us to continue reflecting on these issues.

Reference

Gardner, H. Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

For comments on this essay, I thank Shinri Furuzawa, Annie Stachura, and Ellen Winner.